Inverse Fourier Transform of Continuous Signals

8.2: Continuous Time Fourier Transform (CTFT)

- Page ID

- 22887

Introduction

In this module, we will derive an expansion for any arbitrary continuous-time function, and in doing so, derive the Continuous Time Fourier Transform (CTFT).

Since complex exponentials (Section 1.8) are eigenfunctions of linear time-invariant (LTI) systems (Section 14.5), calculating the output of an LTI system \(\mathscr{H}\) given \(e^{st}\) as an input amounts to simple multiplication, where \(H(s) \in \mathbb{C}\) is the eigenvalue corresponding to \(s\). As shown in the figure, a simple exponential input would yield the output

\[y(t)=H(s) e^{s t} \nonumber \]

Using this and the fact that \(\mathscr{H}\) is linear, calculating \(y(t)\) for combinations of complex exponentials is also straightforward.

\[\begin{array}{c}

c_{1} e^{s_{1} t}+c_{2} e^{s_{2} t} \rightarrow c_{1} H\left(s_{1}\right) e^{s_{1} t}+c_{2} H\left(s_{2}\right) e^{s_{2} t} \\

\sum_{n} c_{n} e^{s_{n} t} \rightarrow \sum_{n} c_{n} H\left(s_{n}\right) e^{s_{n} t}

\end{array} \nonumber \]

The action of \(H\) on an input such as those in the two equations above is easy to explain. \(\mathscr{H}\) independently scales each exponential component \(e^{s_nt}\) by a different complex number \(H(s_n) \in \mathbb{C}\). As such, if we can write a function \(f(t)\) as a combination of complex exponentials it allows us to easily calculate the output of a system.

Now, we will look to use the power of complex exponentials to see how we may represent arbitrary signals in terms of a set of simpler functions by superposition of a number of complex exponentials. Below we will present the Continuous-Time Fourier Transform (CTFT), commonly referred to as just the Fourier Transform (FT). Because the CTFT deals with nonperiodic signals, we must find a way to include all real frequencies in the general equations. For the CTFT we simply utilize integration over real numbers rather than summation over integers in order to express the aperiodic signals.

Fourier Transform Synthesis

Joseph Fourier demonstrated that an arbitrary \(s(t)\) can be written as a linear combination of harmonic complex sinusoids

\[s(t)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} c_{n} e^{j \omega_{0} n t} \label{8.3} \]

where \(\omega_0 = \frac{2\pi}{T}\) is the fundamental frequency. For almost all \(s(t)\) of practical interest, there exists \(c_n\) to make Equation \ref{8.3} true. If \(s(t)\) is finite energy ( \(s(t) \in L^2 \: [0,T]\)), then the equality in Equation \ref{8.3} holds in the sense of energy convergence; if \(s(t)\) is continuous, then Equation \ref{8.3} holds pointwise. Also, if \(s(t)\) meets some mild conditions (the Dirichlet conditions), then Equation \ref{8.3} holds pointwise everywhere except at points of discontinuity.

The \(c_n\) - called the Fourier coefficients - tell us "how much" of the sinusoid \(e^{j \omega_{0} n t}\) is in \(s(t)\). The formula shows \(s(t)\) as a sum of complex exponentials, each of which is easily processed by an LTI system (since it is an eigenfunction of every LTI system). Mathematically, it tells us that the set of complex exponentials \(\left\{e^{j \omega_{0} n t}, \quad n \in \mathbb{Z}\right\}\) form a basis for the space of T-periodic continuous time functions.

Equations

Now, in order to take this useful tool and apply it to arbitrary non-periodic signals, we will have to delve deeper into the use of the superposition principle. Let \(s_T(t)\) be a periodic signal having period \(T\). We want to consider what happens to this signal's spectrum as the period goes to infinity. We denote the spectrum for any assumed value of the period by \(c_n(T)\). We calculate the spectrum according to the Fourier formula for a periodic signal, known as the Fourier Series (for more on this derivation, see the section on Fourier Series.)

\[c_{n}=\frac{1}{T} \int_{0}^{T} s(t) \exp \left(-j \omega_{0} t\right) d t \nonumber \]

where \(\omega_0 = \frac{2 \pi}{T}\) and where we have used a symmetric placement of the integration interval about the origin for subsequent derivational convenience. We vary the frequency index \(n\)n proportionally as we increase the period. Define

\[S_{T}(f) \equiv T c_{n}=\frac{1}{T} \int_{0}^{T}S_{T}(f) \exp \left(j \omega_{0} t\right) d t \nonumber \]

making the corresponding Fourier Series

\[s_{T}(t)=\sum_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) \exp \left(j \omega_{0} t\right) \frac{1}{T} \nonumber \]

As the period increases, the spectral lines become closer together, becoming a continuum. Therefore,

\[\lim _{T \rightarrow \infty} s_{T}(t) \equiv s(t)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} S(f) \exp \left(j \omega_{0} t\right) d f \nonumber \]

with

\[S(f)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} s(t) \exp \left(-j \omega_{0} t\right) d t \nonumber \]

Continuous-Time Fourier Transform

\[\mathscr{F}(\Omega)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) e^{-(j \Omega t)} \mathrm{d} t \label{8.9} \]

Inverse CTFT

\[f(t)=\frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathscr{F}(\Omega) e^{j \Omega t} \mathrm{d} \Omega \label{8.10} \]

Note

It is not uncommon to see the above formula written slightly different. One of the most common differences is the way that the exponential is written. The above equations use the radial frequency variable \(\Omega\) in the exponential, where \(\Omega = 2 \pi f \), but it is also common to include the more explicit expression, \(j 2 \pi ft\), in the exponential. Click here for an overview of the notation used in Connexion's DSP modules.

We know from Euler's formula that \(\cos (\omega t)+\sin (\omega t)=\frac{1-j}{2} e^{j \omega t}+\frac{1+j}{2} e^{-j \omega t}\).

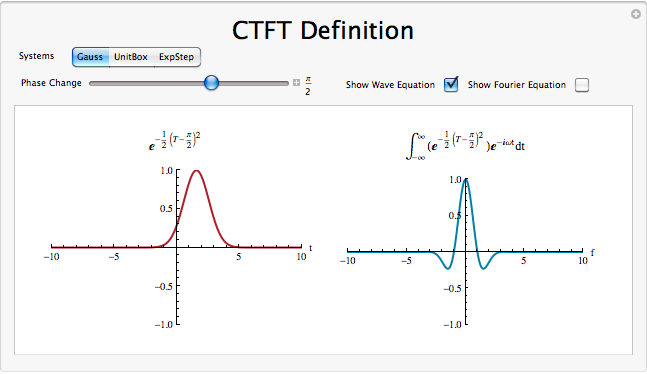

CTFT Definition Demonstration

Example Problems

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Find the Fourier Transform (CTFT) of the function

\[f(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{l}

e^{-(\alpha t)} \text { if } t \geq 0 \\

0 \text { otherwise }

\end{array}\right. \nonumber \]

- Answer

-

In order to calculate the Fourier transform, all we need to use is Equation \ref{8.9}, complex exponentials (Section 1.8), and basic calculus.

\[\begin{align}

\mathscr{F}(\Omega) &=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) e^{-(j \Omega t)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \\

&=\int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-(a t)} e^{-(j \Omega t)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \\

&=\int_{0}^{\infty} e^{(-t)(a+j \Omega)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \\

&=0-\frac{-1}{a+j \Omega} \nonumber \\

\mathscr{F} &(\Omega)=\frac{1}{\alpha+j \Omega}

\end{align} \nonumber \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Find the inverse Fourier transform of the ideal lowpass filter defined by

\[X(\Omega)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}

1 & \text { if }|\Omega| \leq \mathrm{M} \\

0 & \text { otherwise }

\end{array}\right. \nonumber \]

- Answer

-

Here we will use Equation \ref{8.10} to find the inverse FT given that \(t \neq 0\).

\[\begin{align}

x(t) &=\frac{1}{2 \pi} \int_{-M}^{M} e^{j(\Omega, t)} \mathrm{d} \Omega \nonumber \\

&=\left.\frac{1}{2 \pi} e^{j(\Omega, t)}\right|_{\Omega, \Omega=e^{j w}} \nonumber \\

&=\frac{1}{\pi t} \sin (M t) \nonumber \\

x(t) &=\frac{M}{\pi}\left(\operatorname{sinc} \frac{M t}{\pi}\right)

\end{align} \nonumber \]

Fourier Transform Summary

Because complex exponentials are eigenfunctions of LTI systems, it is often useful to represent signals using a set of complex exponentials as a basis. The continuous time Fourier series synthesis formula expresses a continuous time, periodic function as the sum of continuous time, discrete frequency complex exponentials.

\[f(t)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} c_{n} e^{j \omega_{0} n t} \nonumber \]

The continuous time Fourier series analysis formula gives the coefficients of the Fourier series expansion.

\[c_{n}=\frac{1}{T} \int_{0}^{T} f(t) e^{-\left(j \omega_{0} n t\right)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \]

In both of these equations \(\omega_0 = \frac{2 \pi}{T}\) is the fundamental frequency.

Source: https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Electrical_Engineering/Signal_Processing_and_Modeling/Signals_and_Systems_%28Baraniuk_et_al.%29/08:_Continuous_Time_Fourier_Transform_%28CTFT%29/8.02:_Continuous_Time_Fourier_Transform_%28CTFT%29

0 Response to "Inverse Fourier Transform of Continuous Signals"

Post a Comment